When I take on new clients the single biggest training mistake I see is that they just aren’t training hard enough. I’ll explain in the post how I think this happens and what can be done about it

Defining threshold

I assume that if you are reading this you are a reasonably experienced athlete and do not need me to explain training zones. But for clarification I’ll briefly explain what, for the purposes of this article, threshold is and, for the cyclists, sweet spot too.

When most people talk about threshold they are referring to the second lactate or ventilatory threshold. This is sometimes called ‘anaerobic threshold’. Many athletes are unaware of the first threshold also known as the ‘aerobic threshold’. I’ll probably write an explainer at some point on thresholds but for now I am going to focus on the second threshold which, for simplicity, I’ll mostly refer to as ‘threshold’.

What is threshold?

Threshold is the point above which a small increase in pace results in a very large increase in blood lactate production. To confuse matters there are many methods for measuring this point and analysing the data. None of these is the same, so, when athletes discuss ‘threshold’ with each other they could very easily be referring to very different things.

We can loosely define threshold as a pace or power output of a hard effort that can be sustained for between 20 to 60 minutes. I appreciate this definition is a bit vague but unfortunately that is where exercise science leaves us.

Functional Threshold Power (FTP)

If you’re a cyclist then you’ll recognise my definition incorporates functional threshold power (FTP).

FTP is the highest average power output sustained during a one hour all-out time trial. In practice riding a one hour time trial requires a lot of skill and motivation. To make things a little easier the 20 minute test was developed. This is still an all-out effort but being shorter can be easier to pace. FTP is determine by taking 95% of the average 20 minute power.

Finally, another popular training intensity that cyclists employ is sweet spot. This is from 88-93% of FTP making it a form of tempo training but not full threshold training.

Threshold as a marker of performance

When scientists first investigated the relationship between blood lactate and exercise intensity they naturally became very interested in the point we now know as threshold. It was clear that exercise below threshold could be sustained for a long duration whereas exercise above threshold was limited to a few minutes. This clearly opened up a plethora of questions about exercise metabolism and fatigue. A topic that is rigorously studied to this day.

In addition to these studies there was much interest in the relationship between the pace or power output at threshold and performance. Numerous researchers reported that athletes who could sustain a higher pace at threshold were likely to run, swim, cycle, row and ski faster in competition than those who had a lower threshold pace. It was also shown that pace at threshold can be a better predictor of performance than maximal oxygen uptake in elite athletes. Thus the obsession of coaches with thresholds began.

Threshold as a training intensity

Given that threshold is highly correlated with performance curious coaches and exercise scientists started to explore whether there was any benefit of training at threshold. Studies as far back as the 1980s & 1990s were already suggesting that training above the lactate threshold brought about greater improvements in fitness. But this is where the story potentially gets more complicated.

Designing training studies is fraught with problems because there are many variables to control. For example we can’t study whether threshold training is optimal without also considering if there is also an optimal distribution of training intensities. That is, if an athlete dedicates a certain amount of time to threshold training should they also perform training at other intensities above and below threshold, and for how long?

This is clearly tricky to unpick as there is a continuum of intensities to choose from. Not only does one have to consider the proportion of training spent at any given combination of intensities but also the effect of various training methods: different types of intervals or continuous training. Given the length of time required for an athlete to adapt to training it could take a very long time to investigate all of these combinations.

Polarised training

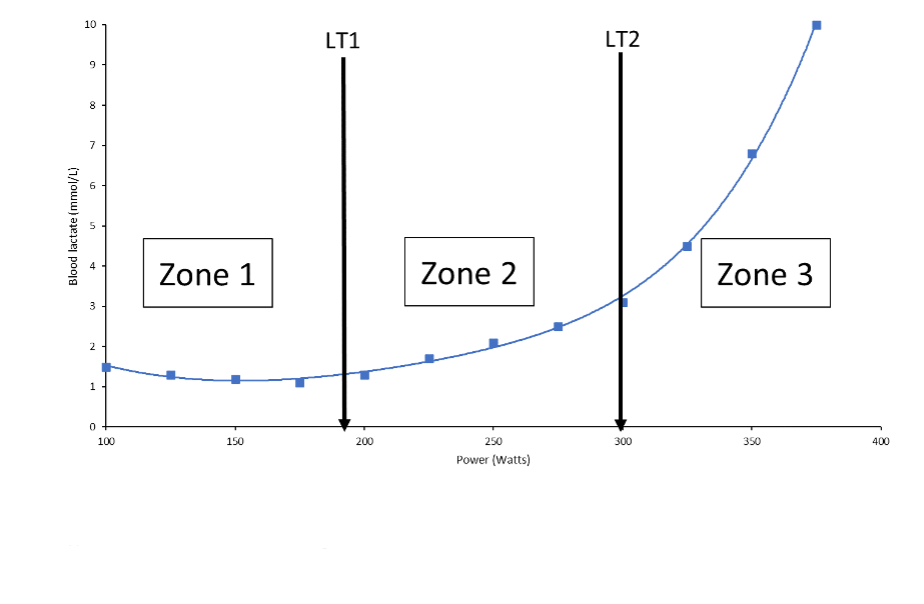

One way of dealing with the issue I have described is to define discrete training zones and this is where first and second thresholds have been useful. I’m momentarily going to break with my terminology and consider thresholds one and two (see image).

Generally speaking, all multi-zone systems originate from the original three zone system. Zone 1 is up to the first threshold, zone 2 is between first and second thresholds and zone 3 is above the second threshold. This gives us low, medium and high intensity training (LIT, MIT and HIT, respectively).

Without entering into a protracted discussion, applied practice and research seem to suggest that endurance training is best polarised. For an endurance athlete that means 80% or more of their training should be LIT. With 20% or less is dedicated to HIT efforts above the second threshold.

Depending upon where you look for advice you’ll see that these proportions vary slightly. I’ve seen elite cyclists’ programmes described at conferences where approximately 85% is LIT with the remaining 15% split equally between MIT and HIT.

That these proportions vary suggests to me there is a lot of individual variation in what works for athletes. Or that there isn’t a clear cut answer so coaches and athletes are experimenting.

Most people need harder training

Although this approach has been recognised and written about for more than 20 years, and early lactate threshold studies suggest training above threshold is more beneficial, many people are just discovering polarised training. I regularly read training advice on the internet and much of it still describes threshold models and this is particularly true of time trial training. I’ve even seen programmes coaches have set that are described as polarised but are, in fact, a threshold model. There seems to be a mental block for many when it comes to fully polarising training.

That is not to say that threshold training doesn’t work and can’t be part of the armoury. Threshold training can be beneficial for fine tuning race pace prior to competition, adding variety to training and for those days when an athlete can’t face the super high intensities required of HIIT. A small prescription of threshold work may also promote better lactate clearance.

I use threshold from time to time for these reasons, but I see riders falling into a trap where they generally aren’t training hard enough and consequently lack polarisation in their training. In my experience, regardless of whether the training is polarised in the proportions I describe above or not it, is the introduction of proper HIT that seems to have the greatest impact.

Training intensity mistakes

There are two training mistakes people tend to make. Firstly, the slow stuff just isn’t slow enough and the hard stuff is too easy. The training meets in the middle and, although it improves fitness at first, there comes a point of stagnation. Athletes and coaches attempt to overcome this stagnation by increasing the volume of threshold work but that has minimal effect. Increasing sweet spot training is another strategy I’ve seen employed but this tends to lead to overtraining – I’ve dealt with the aftermath created by other coaches. The only effective way to make progress is to adjust the training distribution which usually involves adding HIT.

The second training mistake is to train in zones and fail to consider pace. Modern training software encourages coach laziness as generic sessions can be written in advance. The structure of the session and the training zone of each interval can be made into a template which is then dropped into multiple athletes’ calendars. At lower exercise intensities this may be okay (although I don’t do it) but at higher intensities the pace isn’t specific enough. For example, the threshold training zone can be pretty broad, covering sustainable paces of 20-60 minutes. 3 x 10 minutes at 20 minute pace is going to be very different to the same interval at 60 minute pace. Furthermore, the physiological responses for two athletes can be very different, even within the same zone.

Not all threshold training is equal

Something I have recognised for many years and is being borne out by current research is that athletes can respond to the same relative intensity very differently. In other words, the coach thinks they are setting the same relative intensity but they may not be. Two athletes may have different paces or power outputs at their threshold but there is an assumption that their perception of effort and physiological responses would be similar.

Automated training apps and coaches with large numbers of clients rely upon this principle to set training. It gets complicated if everyone responds in a different way, but this is precisely my experience.

A coach can’t set sweet spot or threshold training and assume the effect will be the same for everyone. You may have even experienced this yourself. Have you ever shared your favourite training session with a friend and they physically can’t do it and yet you find it doable? I know of coaches perplexed by this and they don’t understand why but continue to prescribe training in the same way. Of course, the solution is to tailor every session to every rider.

The best athletes and coaches knew it all along

It’s interesting to occasionally read old coaching manuals and articles with athletes. In fact, I think it is an essential requirement of a good coach to review their methods and compare the new research with established methods. In many cases current research throws light upon why old training regimens worked, or not, as the case may be.

I’ve just finished reading the book The Obree Way written by former Men’s World Hour Record holder Graeme Obree. You may remember he invented the tuck arm position and used parts from a washing machine to fabricate his own bike. In his books he describes a method where he rides on the indoor trainer for 20 minutes trying as hard as he can to beat his previous workload. Chris Boardman, his rival in the 1990’s describes similar sessions where he pushes the envelope of what he can achieve.

Of course, the whole principle behind interval training is to train harder for a longer distance than you might manage if you were to train continuously. Emil Zatopek understood this and his training arguably popularised this method. He ran very long sessions made up of dozens or 200 and 400 m reps. Today we would call this high intensity interval training (HIIT) but Zatopek did it in the 1940s and 50s.

In running or swimming, pace has always been used for setting intervals although this has somewhat been forgotten in cycling. There will be sessions where the athlete is encouraged to beat their previous best pace, so called ‘best set’ intervals.

The benefits of HIIT

HIIT training has been extensively researched and the benefits are many fold. Obviously there are many different protocols each with slightly different benefits. But given a mix of different HIIT protocols in your training you can expect to see improvements in VO2max, economy/efficiency, buffering of acid in skeletal muscle, lactate clearance, utilisation of fat, anaerobic metabolism, heart rate recovery, peak aerobic power, plasma volume, cardiac function, ventilatory function, vascular function etc. The list is pretty extensive!

These underlying physiological changes are interesting but for the athlete the most important improvement afforded by HIIT is an increase in their performance. Numerous studies demonstrate this, as does my own experience as a cycling coach. There is also the psychological benefit of learning to push your boundaries in training so you can replicate the same effort in a race.

How to set HIIT

My approach is to set on average 2-3 HIIT per week. In the early phases of the preparatory training cycle I tend to set perhaps only one HIIT per week but build fairly quickly to two HIIT per week. If I feel the athlete needs a hard week this may rise to three sessions.

To ensure the athlete is working hard enough I like to see HR climbing to 90 – 95% of maximum heart rate. Different interval sessions can give slightly different HR responses so it is important to monitor the data to ensure the desired response is obtained.

For the most part the intervals I set are ‘best sets’. That is, the athlete has to achieve their best possible pace or power output over the set. The next time they train they have to match or better those numbers. With my experience I am able to prescribe the right combination of intervals and not have to test very often. If the athlete performs well on a given session I’ll know whether that relates to improved aerobic or anaerobic performance. I test from time to time but it usually only confirms what I already know. This is a further benefit of using this kind of approach.

Types of HIIT

I think I will write a further post to cover types of HIIT and the potential benefits of each. For now there are three categories of HIIT I use: anaerobic, short aerobic and long aerobic. Be aware that other authors’ definitions may vary – this is my approach.

Anaerobic HIIT sessions are efforts from 5 seconds to 1 minute and usually have long recovery intervals so each effort can be performed with near maximum intensity.

Short aerobic HIIT, sometimes called micro-intervals, are very short efforts with frequent, short recoveries. Popular efforts (in seconds) are 30:30, 30:15, 20:40: 20:40. These can be good for raising heart rate for long periods of time.

Long HIIT are intervals from 2 to 8 minutes put together in sets of equal duration intervals, ladders and pyramids e.g. 8 x 5 mins or 8,7,6,5,4 mins. These are the most common intervals I set and typically have recovery intervals of 2-3 minutes. These intervals are important in developing pacing ability and tolerance to sustained efforts.

Summary

Threshold training has its place but not everyone responds in the same way to threshold training. Too much MIT can lead to stagnation and possibly overtraining if the volume of training is increased to address the lack of improvement.

Programmes with too much MIT benefit from the introduction of HIIT and a reduction in the intensity of the remaining training. This is in accordance with the principle of polarisation although, in my experience, the precise ratios of HIT to MIT don’t necessarily need to be met.

HIT has many physiological benefits and overall improves performance. It provides the opportunity to keep track of improving performance without having to test so frequently. Furthermore HIT has the additional benefit of teaching an athlete to push to their limit which is a large advantage when they come to race.

To incorporate HIIT into your training programme aim for two sessions per week and an occasional three sessions to make a hard week. All other training should be scheduled around the HIIT. An amateur athlete with a job or in full-time education may consequently do more HIIT as a proportion of their weekly training volume compared with an elite athlete who will complete a greater volume of LIT.

If you have found this article interesting and you would like help with optimising your training please contact me.