When I started out as a cycling coach it is fair to say hardly any cyclists knew about polarization. But did you know highly decorated British cyclists Nicole Cooke followed a polarized plan?

Now it is a hot topic with whole websites devoted to the principles of polarization. But what is it? And is it suitable for you?

Discovering Polarization

Prof. Stephen Seiler is largely responsible for identifying and popularising the method. I first became aware of polarization in 1999 when I found Seiler’s old Masters Athlete Physiology and Performance website. I was studying for a masters degree in sports science and had to write an endurance training programme as an assessment. Although I had learnt a lot about training and periodisation, I struggled for information on the best training distribution. That is, the proportion of training time devoted to low, medium and high intensity training.

Seiler’s site described his observations of the training practises of Norwegian skiers and runners. He noticed how these athletes would perform their endurance training strictly keeping the pace low. Even to the extent that they would walk or ski-walk up steep hills. In contrast, their intervals were conducted in small amounts at very high intensity. When quizzed about this, the athletes and coaches explained this approach gave the greatest improvement in fitness for the effort.

Defining Polarization: the 80:20 rule

You’ll often hear polarised training described as ’80:20 training’. That is, 80% of your training prescription is dedicated to low intensity (endurance) training (LIT). You are then advised to make up the balance of your time with high intensity training (HIT). This prescription of HIT usually comprises high intensity interval training (HIIT). Incidentally, strength training is counted separately.

You’ll find that polarization differs from so-called ‘threshold’ models because little time is devoted to medium intensity training (MIT). Terminology varies, but middling intensities include tempo training, sweet spot and anaerobic threshold paces. It’s thought that polarization is effective because it taps into the optimal balance of biochemical signals which improve fitness.

What are the polarized training zones?

If you research different training zone systems they can be extremely confusing. You’ll discover numerous ways of determining training zones, and variation in the number of zones employed. There are also lots of terms that seem to explain similar things but they aren’t always interchangeable. I could easily devote several pages to describing fitness tests and zone systems.

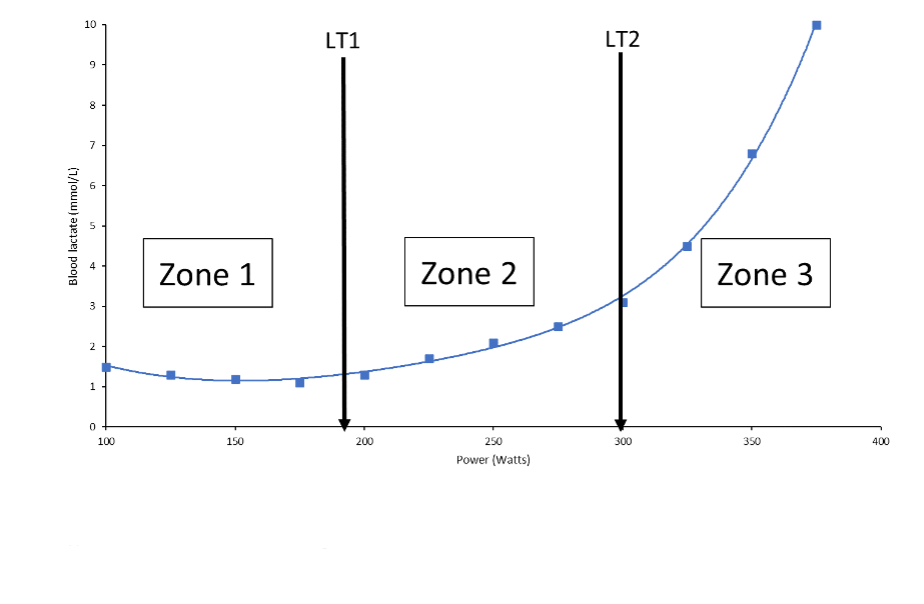

Very simply, most zone systems originate from measures of blood lactate which I explain in another post. The figure below is taken from that article and illustrates the three zones that are obtained:

Z1: Low intensity aerobic training (LIT) up to the aerobic threshold (LT1)

Z2: Medium intensity training (MIT) up to the anaerobic threshold (LT2)

Z3: High intensity training (HIT) above the anaerobic threshold (>LT2)

Even with this approach you’ll see some variation. In running and cross-country skiing fixed blood lactate markers of 2.0 and 4.0 mmol/L have been used interchangeably with LT1 & LT2. However, there is a lot of individual variability and these markers may not be appropriate for cycling.

Is 80:20 a hard rule?

I understand this ratio was figured out by Norwegian coaches and sports scientists by carefully monitoring athletes’ responses to training. They found that training gains were optimal when HIT and LIT volume were distributed in this way. But the simple answer to the question is ‘no’, I don’t think it is a hard rule.

I have attended many endurance conferences where speakers have described athlete case studies and the respective training zone ratios. LIT makes up around 75 to 85% of training volume with differing proportions of MIT and HIT forming the balance. Note that it’s actually common practice, even with polarized training, to see a good dose of MIT prescribed in cycling. A ratio I’ve seen reported a few times is roughly 7% HIT, 7% MIT and 86% LIT.

In my experience it is rare for elite cyclists to achieve an 80:20 split because of the sheer quantity of HIT they would have to complete. Imagine a 30 hour week with 6 hours of HIIT! Not only is that physically taxing but it is also psychologically very demanding.

On the other hand, time-crunched amateurs and younger cyclists training lower volumes often get closer to 10 to 20% HIT. You only have to complete a couple of mid-week HIIT sessions within a 10-hour training week to achieve these proportions.

The measurement problem

A significant issue around quantifying polarized training is how you go about measuring the time spent in each zone. This isn’t straightforward as there isn’t a single accepted approach. Whether your training appears polarized or not could be influence by how you determine your training thresholds, the training zone system you use and how you go about quantifying training intensity within a workout or race.

We’ve already touched on the first two points, so let’s think about measuring training intensity. There are several options available but the most common instantaneous measures are heart rate, rating of perceived exertion (RPE) and power output. You could use blood lactate, but it is less convenient and doesn’t provide a continuous measure. Although that could change with development of continuous monitors.

All training software packages provide time in zone by power and heart rate but I rarely see the two tally. A key problem with this ‘binning’ approach is that power and heart rate respond to changes in effort at different rates. Power fluctuates instantaneously in response to your pedalling, whereas your heart rate responds much more slowly. Consequently, small changes in effort can cause power to flit rapidly between zones but your heart rate may deviate very little. What looks polarized by one measure may not appear to be by the other.

Due to issues with binning, alternative approaches have been proposed.

Polarization by session RPE

I have previously written about the usefulness of perceptual measures to quantify training intensity, such as the rating of perceived exertion (RPE). With RPE you simply rate how hard the exercise feels on a scale from complete rest to maximal effort. Most often this is on a 10-point scale.

The session RPE (sRPE) is a development of this idea where you score the average RPE for a whole workout. The best approach is to rate the session 30-minutes after completion so all the elements of the workout ‘blur’ into one. To estimate the overall load you multiply by RPE by the number of minutes spent training. This is a surprisingly effective way of measuring training load and has been shown to successfully quantify the level of polarization in training plans.

The session goal approach

A further method is to quantify training by ‘session-goal’. That is, workouts are categorised according to whether they are steady state, threshold or interval training.

To validate this approach, researchers plotted training intensity distribution for a large number of athletes using both the session-goal approach and sRPE. When they compared the fraction of time spent performing LIT, MIT and HIT with both approaches there was very close agreement. This means you could use both session-goal or sRPE interchangeably to measure the level of polarization in your training.

A criticism of these different approaches is that it is possible to change the method to get the result you expect or would like. I think this is a valid concern but I instinctively prescribe training by session goal. If other coaches do the same then it’s arguably valid to measure polarization in this way.

Polarized training is a philosophy not an accounting system

The measurement problem used to bother me a great deal when I first used polarized cycling coaching. But through experience I learned I could significantly improve my cyclists’ fitness without having to worry about exact ratios. Long before researchers defined the session-goal method pragmatism led me to the same approach.

As with much of my applied practice, polarized cycle training caused me a few headaches in the early days. However, this didn’t put me off and I soon concluded that it was best treated as a philosophy, not an accounting system. It’s more important to prescribe the correct components of training at the right frequency than to obsess over ideal ratios.

I first schedule a suitable volume and frequency of HIT and MIT for the training week. Following this, strength, core, technical work, and mobility training are programmed. Once those elements are in place I build LIT. This could be dedicated LIT sessions or LIT added to another workout. For example, topping and tailing an interval session with easy endurance. I then review the training to ensure the various session are in the right balance. If the week appears polarized then that is good enough – in my opinion.

Is polarized training for me?

In my experience, most cyclists respond well to some form of HIT training. But it doesn’t necessarily follow that everyone should be following polarized plans. In fact, there are plenty of examples of highly successful athletes who don’t use polarized methods. And, although I have built a reputation as a polarized coach, I train some athletes using a threshold model. Why? Because everyone is different and I have discovered that threshold training works better for them.

I’ve learnt over my career that sport science is a long way from describing the optimal training prescription. So I think it is wrong for sports scientists, or coaches, to argue dogmatically for one approach over another. I have argued here for most athletes to train harder as HIT has many benefits, but I’d be naïve to think that polarization is universally applicable. HIIT is both physiologically and psychologically tough with some athletes having a higher tolerance for it than others. Some people simply can’t cope with the volume of HIIT required to achieve polarization. But, then again, it depends how you measure it!

Employ some pragmatism and experiment

I think the most important piece of advice I can give is to take a pragmatic approach to training distribution. If you are a coach it is important to be attentive to your athletes needs and evaluate what works for them. It’s good to experiment a little to discover the most effective approach and to keep an open mind. In the years I have been coaching I’ve witnessed many trends. Some stick, some go, and others seem to follow in cycles. As coach or athlete, if you aim to think objectively you’ll find solutions to the programming problem more quickly. After all, coaching is a process of problem solving and discovery.